Am I a Researcher or a Salesperson?

I can’t help but find poster presentations at major research conferences amusing, or at the very least chucklesome.

Drifting through a labyrinth of display walls with some 300 or so posters and researchers standing by eagerly waiting to present their work can make for a terribly awkward experience. If you haven’t scanned the roster and identified posters you’re interested in ahead of time, you’re left sliding from one poster to another—slow enough to be able to read the title and decide if you’d like to stop by but fast enough to be able to move on if you find that it’s not your cup of tea (that is, without crushing the hopes of the researcher standing idly by).

Being on the other side is not any easier. When I was at a conference recently presenting a poster of our work, as I diligently stood by my poster, hoping someone would stop, many a time I found myself in what can only be described as a staring contest with other conference-goers as they decided whether they’d like to hear me go through my work or answer any of their questions. This stand-off would often cease when they decide it’s not for them—much to my disappointment. Here, I will happily acknowledge any counterarguments that the passerby may have read my poster and may have had no questions or comments to share with me. I will now swiftly refute such a counterargument on the grounds that no human or machine is able to read 500 words in 3.62 seconds.

When people do stop by your poster, it is often because they may be working in a similar area of research and find your work relevant to them. They might want you to take them through your work or have specific questions based on their work and experience. These moments tend to be the highlights of conferences. You get to meet new people who have committed a part of their life—regardless of how big or small—researching and exploring the same things you’ve dedicated a part of your life exploring. That is to say, it’s not all that bad!

Let’s Become a Salesperson!

But I couldn’t help but let a tiny thought roam free in my mind: what if I treated this as a sales pitch? What if, for just the few hours while I’m standing here in front of my poster, I pretended to be a salesperson. The product? My research. The buyer? Ordinary conference-goers.

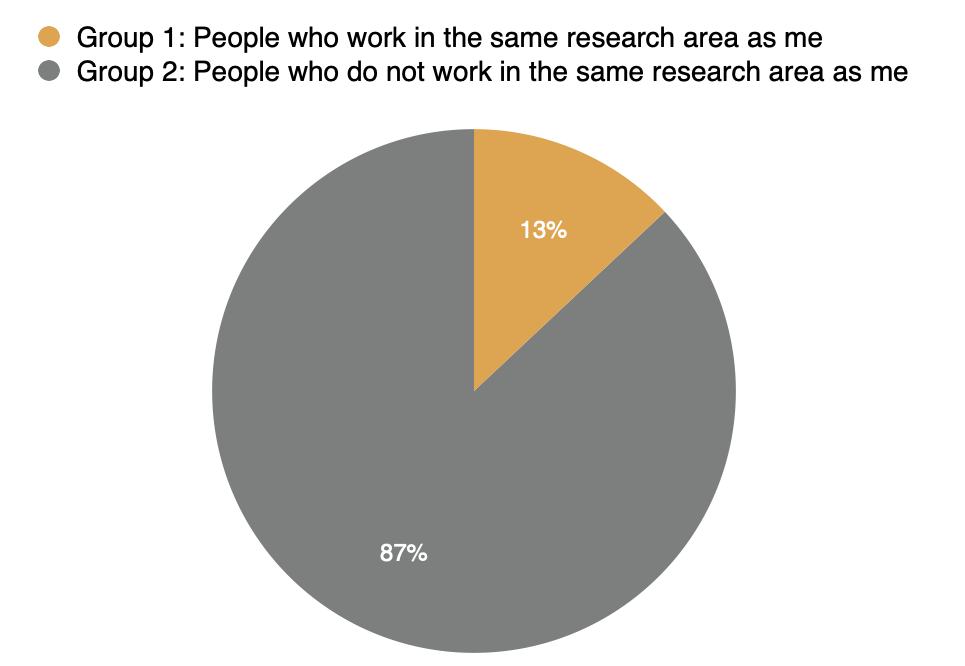

Let’s say we segment customers (conference-goers) into two distinct groups. This is shown in Figure 1.

In general, Group 1 will tend to be a significantly smaller percentage of conference attendants than Group 2 (depending, of course, on how broadly you define research area and the type of conference you’re at).

Why should I stand by idly and let my poster sell itself? An overwhelming majority of the people who will then visit, ask questions, and engage with my work will be from Group 1 and especially those who work in the sub-sub-sub… field that I do research in. Same logic as putting your product out on the market and doing minimal marketing. The only person who will come across it is the buyer who is specifically looking for what you have to sell.

But I can guarantee that there is some portion of conference-goers in Group 2 who may be interested in what I am selling but don’t know it yet. We may share a general area of research—even if it is not a near-perfect match. They might not realize that they’re actually in the market for my ideas and all they need is a little pull.

(Incomplete) Guide to Selling Research

Instead of standing by passively, what if you engaged and interacted as people passed by. Someone taking a peek at your poster as they walk by? Catch them off guard with a “Stop by and trust me, it will be worth your time…” or at the very least be proactive and say something along the lines of “You seem interested! Want me to take you through?”

If someone is staring for a while and it seems they can’t decide whether they should stop by, mix together some humor, a good dose of confidence, and a “you’ve stared too long not to have at least one question” and you may end up starting a conversation over your work with someone who otherwise would have passed on.

Or, just have a classic elevator pitch on stand-by: “Give me 2 minutes of your time and I’ll convince you that…“. Tailor your elevator pitch based on what you’re presenting and the type of conference you’re at. For example, if you’re presenting an application where you use a classic, efficient ML method instead of the latest from deep learning (do excuse me for anchoring my examples around AI & ML), maybe lead with “I’m sure you’ve heard plenty of blabber about neural networks, but why go there if a simple SVM works? This is what our team aimed to show in…”

The moment I switched from passively standing by my poster to actively trying to engage and bring in passersby, the number of people who stopped by, asked questions, and heard me speak about my work vastly jumped. More people to share your work with = more people to connect with and learn from (and the latter is principally what conferences are all about!)

It doesn’t need to be said but please don’t hound passersby (nothing is worse than finding yourself stuck in a lecture you didn’t ask for) but don’t sit by and wait for your product to sell itself.

Attention and “The Big Bet”

More broadly, my early impression is that there is a strong onus on every researcher to advocate and market their own paradigm–often in order to “out-sell” competing paradigms. The way you “sell” your research could be in the form of engaging more attendees at poster presentations, but it goes beyond that and has severe ramifications in how many new researchers enter your research domain, align with your ideas,

How will we truly arrive at reasoning artificial intelligence models? Is it through:

- embedding causal models of thinking?

- building physically-informed world models?

- working with language or video?

- trusting in chain-of-thought?

Behind each of these possible directions are groups of researchers who have dedicated their life to their respective hypotheses, often through volumes of papers (and plenty of time!).

Who wins this marketing game shapes the future of research. The paradigm that comes off as the most promising, viable, and exciting may be in line to receive more external funding. It may receive more attention. It may have workshops dedicated to it at major conferences. And these are undeniable contributors that accelerate the growth of a research field (both in interest but also in the number of active researchers and students entering that research domain). The self-propagating cycle that this engenders, I’m sure, is self-evident.

Research horizons aren’t measured in months or quarters, but in years and decades. It can take decades for your ideas to truly blossom and take shape and to feel like you have moved the needle in your field of research. This can make it feel like selecting and backing a paradigm to dedicate your life to building is a big bet. Who knows how it will play out? And what happens if you are wrong?

These ideas have long been present and, in fact, there is a rich meta-literature that comments on this (see: Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and Paul Feyerabend in Against Method). What I have to show here are simply the reflections of a soon-to-be PhD student navigating a wide and explosive field.

So, maybe every researcher is, in part, a salesperson.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: